Kunst, Könige und Klassenschranken – ein Tag in Kathmandu

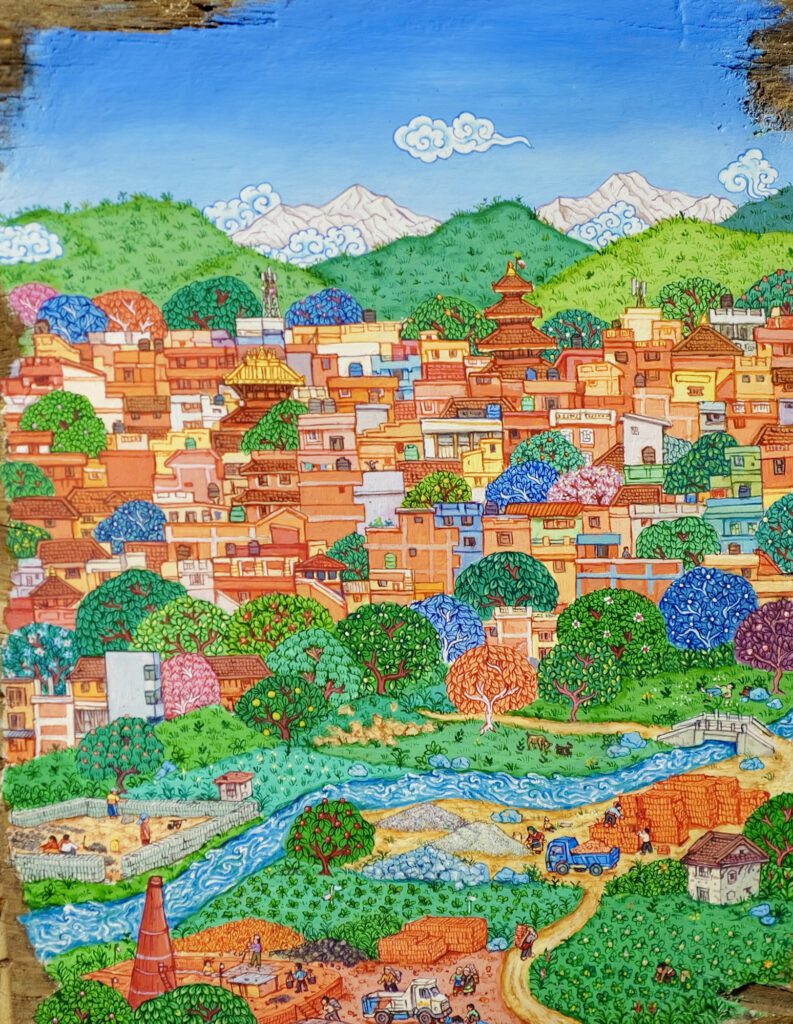

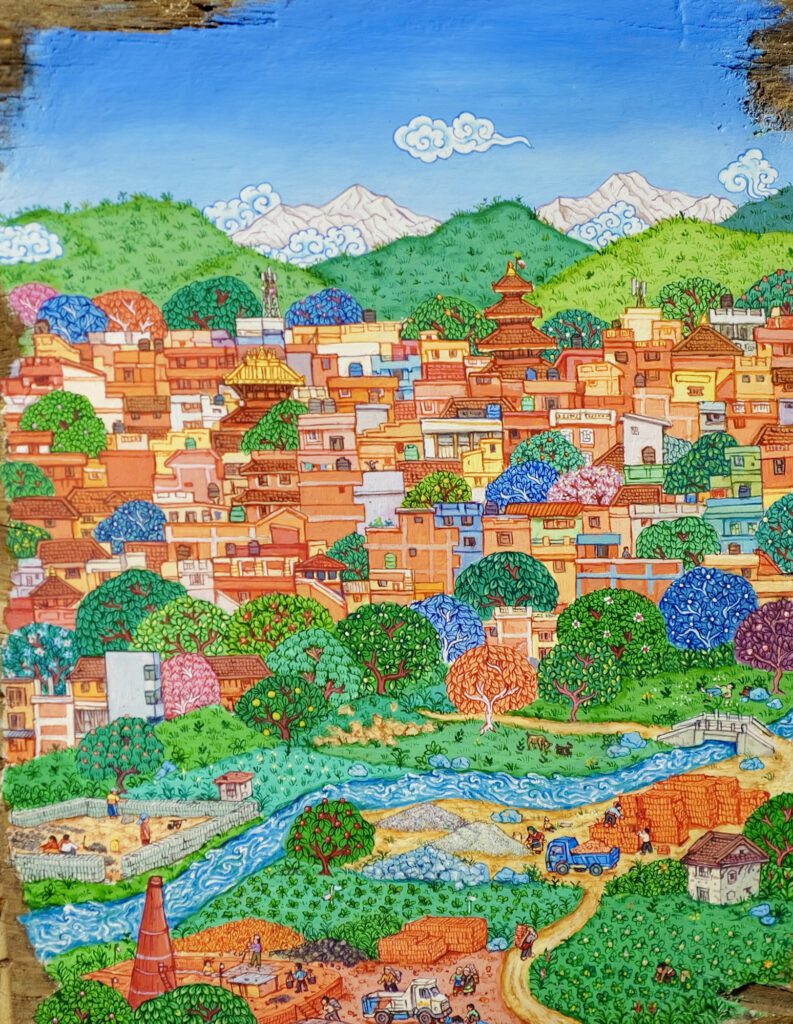

Nach unserem Besuch im Nepal Art Council zog es uns weiter zur Siddhartha Art Gallery, einer der wohl feinsten Adressen für zeitgenössische Kunst in Kathmandu. Sie liegt im Baber Mahal Revisited Complex, einem architektonischen Juwel mit kolonialem Einschlag – einst Teil des Palastareals der Rana-Dynastie, heute eine luxuriöse Oase für Kunstliebhaber, Gourmets, Expats und solche, die es sich leisten können.

Was von außen wirkt wie ein verputztes Nebengebäude aus britischer Kolonialzeit, entfaltet sich im Innern als Kultur-Oase mit royaler Patina. Weiße Fassaden, Ziegeldächer, kunstvoll geschnitzte Holztüren und -fenster – der ganze Ort wirkt wie aus der Zeit gefallen. Zwischen Galerien, gehobenen Boutiquen und edlen Restaurants spazieren Besucher, deren Designerkleidung mehr kostet als ein Monatseinkommen eines Lehrers.

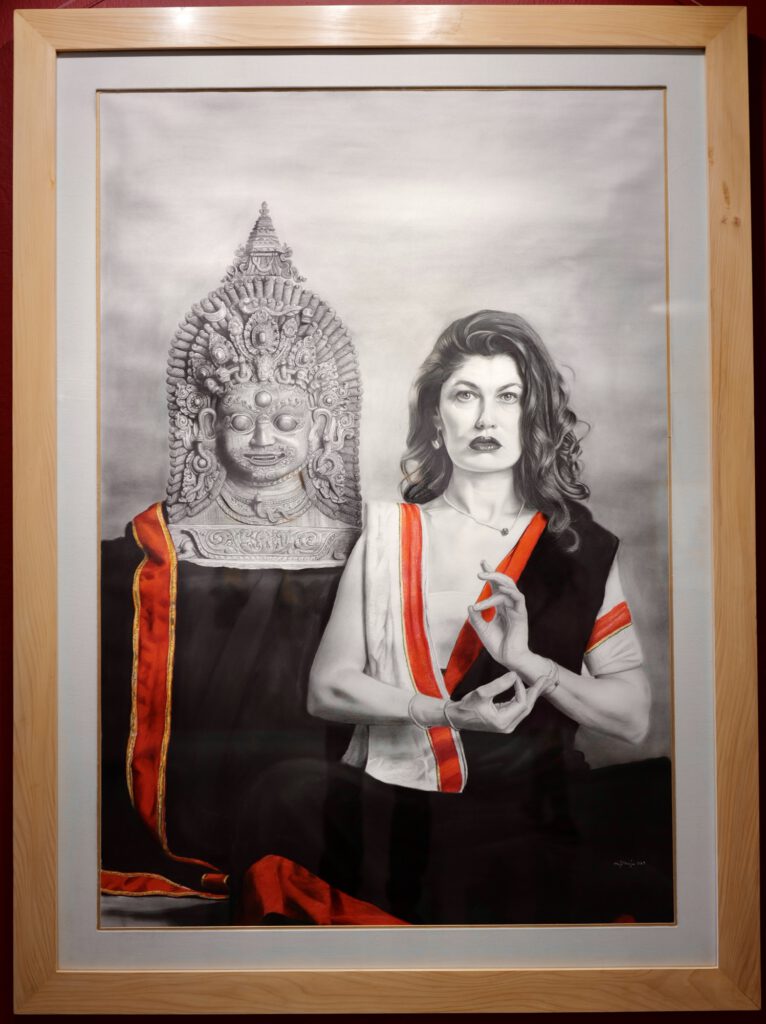

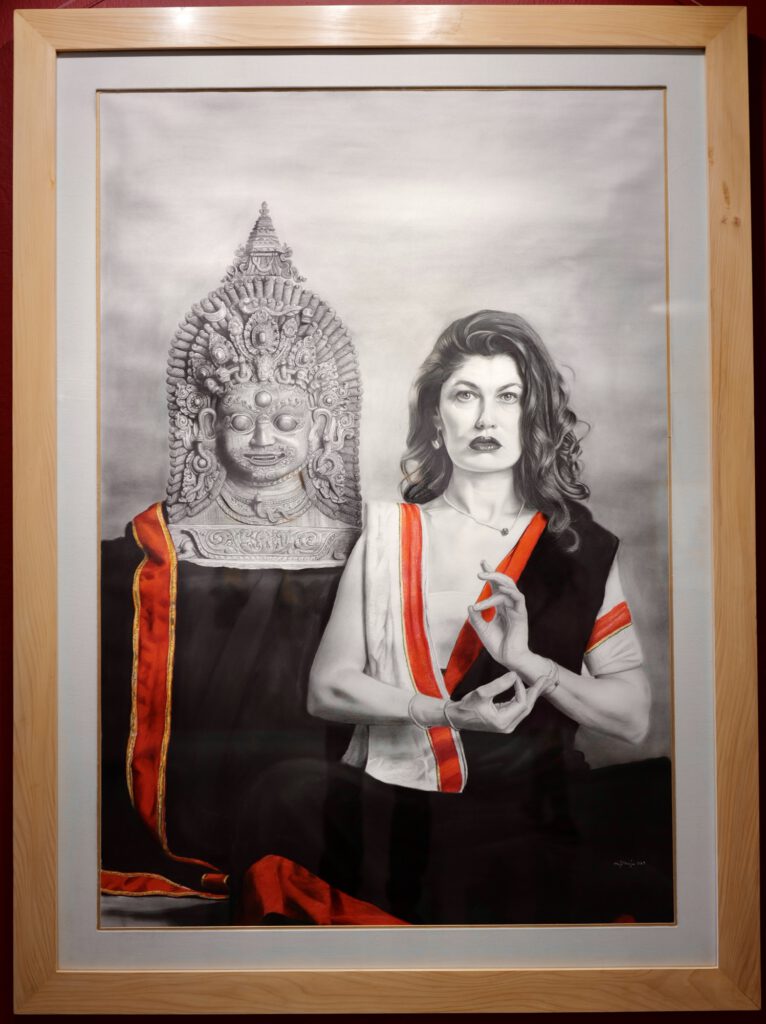

Im Gespräch mit der Besitzerin der Siddhartha Art Gallery wurde schnell deutlich, mit wie viel Idealismus – und Geduld – sie ihre Arbeit betreibt. Seit 1987 führt sie die Galerie mit dem klaren Anspruch, ausschließlich zeitgenössische Kunst zu präsentieren. Keine Touristenkunst, keine Buddhas auf Massenleinwand, sondern Werke lebender Künstler, die sich mit der Gegenwart auseinandersetzen. Sie erzählt, dass einige wenige wohlhabende Nepalesen bereit seien, zigtausend NPR (mehrere Tausend Euro) für kunstvolle Statuen und Objekte mit religiösem Symbolwert auszugeben – für Götterfiguren aus Bronze oder Holz etwa. Doch für abstrakte Malerei oder gesellschaftskritische Installationen aus Bhaktapur – woher übrigens die meisten ihrer Künstler stammen – fehle häufig das Verständnis. Oder vielleicht schlicht das Interesse. “Zeitgenössische Kunst verkauft sich schwerer”, sagt sie nüchtern, “weil sie keine Gottheit darstellt, an die man Weihrauch opfern kann.” Und so bleibt ihre Galerie ein Ort für Liebhaber – und für eine Hoffnung, dass sich der Kunstbegriff irgendwann ebenso weiterentwickelt wie das Land selbst.

Und damit sind wir auch schon bei einem frappierenden Kontrast: das soziale Gefälle, das einem hier geradezu ins Gesicht springt. Die Preise der Speisekarten sind Einladung und Abgrenzung zugleich. Wer hier Kaffee trinkt, zeigt automatisch, dass er nicht zum Rest gehört. Dass dieses Gefälle nicht nur wirtschaftlich, sondern auch historisch gewachsen ist, macht der Ort selbst sichtbar.

Denn der Baber Mahal-Komplex trägt den Geist der Rana-Ära in sich. Diese herrschte in Nepal von Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts bis 1951 autoritär über das Land – mit dem Ziel, Macht durch Monopolisierung von Bildung und Information zu sichern. Die einfache Bevölkerung wurde systematisch vom Zugang zu Wissen ausgeschlossen. Eine gebildete Masse hätte zu gefährlich werden können – so die Logik der Herrschenden. Der Preis dafür: ein bis heute spürbarer Rückstand im Bildungssystem.

Diese dunklen Schatten der Vergangenheit sind längst nicht verflogen. Auf dem Weg zur Galerie zogen Lehrer-Demonstrationen an uns vorbei – fordernd, laut, aber friedlich. Es ging um nichts weniger als Job-Sicherheit für Pädagogen. In einem Land, in dem ein studierter Lehrer zwischen 30.000 und 48.000 NPR verdient (umgerechnet etwa 210 bis 340 Euro im Monat!), verdienen andere Staatsbedienstete deutlich mehr – ohne dieselbe gesellschaftliche Verantwortung zu tragen. Und dennoch können Lehrer derzeit jederzeit entlassen werden – ein Arbeitsverhältnis auf dünnem Eis.

Dabei ist Bildung doch das A und O – nicht nur für persönliche Entwicklung, sondern für die Zukunft eines ganzen Landes. Doch stattdessen scheint das eigentliche Karriereziel vieler junger Nepali ein Studium im Ausland zu sein. Und danach? Möglichst weit weg – Arbeit in Australien, Kanada oder Europa. Nepal exportiert seine klügsten Köpfe – freiwillig, aber aus Notwendigkeit. Das mag kurzfristig Devisen ins Land bringen, langfristig aber verliert ein Land seine Seele, wenn Bildung nicht zur Heimatbindung führt, sondern zur Flucht.

Und das frustriert mich. Denn dieses Land hat alles: Schönheit, Geist, Geschichte, Natur – aber es verliert seine Jugend, seine Lehrer, seine Hoffnungsträger. Und das ausgerechnet in einem Zeitalter, in dem Bildung entscheidend ist für gesellschaftlichen Aufbruch, wirtschaftliche Entwicklung und demokratische Stabilität.

Natürlich bleibt einem der Humor als letzte Überlebensstrategie. Also trinke ich auf das Ganze einen – zugegebenermaßen sündhaft teuren – Espresso im Baber Mahal und frage mich:

Wie viel Kunst braucht ein Land, das seine Lehrer entlässt?

Oder umgekehrt: Wie viel Bildung braucht ein Land, um echte Kunst zu verstehen – und zu fördern?

Beides hängt miteinander zusammen. Leider oft nur in der Theorie.

English version below

Art, Aristocracy, and Inequality – A Day in Kathmandu

After our visit to the Nepal Art Council, we made our way to the Siddhartha Art Gallery—arguably one of the finest addresses for contemporary art in Kathmandu. It’s located in the Baber Mahal Revisited Complex, an architectural gem with a colonial touch. Once part of the Rana dynasty’s palace grounds, it’s now a luxurious retreat for art lovers, gourmets, expats—and those who can afford it.

What looks from the outside like a plastered annex from the British Raj era reveals itself inside as a cultural oasis with a royal patina: white facades, tiled roofs, intricately carved wooden doors and windows. The whole place feels like it’s slipped out of time. Visitors stroll between galleries, upscale boutiques, and elegant restaurants—dressed in designer clothes that easily cost more than a teacher’s monthly salary.

In conversation with the owner of the Siddhartha Art Gallery, it quickly became clear how much idealism—and patience—drives her work. Since 1987, she’s run the gallery with the express goal of showcasing contemporary art only. No tourist kitsch, no mass-market Buddhas on canvas, but the work of living artists engaging with the present. She explains that while a few wealthy Nepalis are willing to spend tens of thousands of NPR (several thousand euros) on ornate statues and objects with religious symbolism, there’s far less interest—or understanding—for abstract painting or socially critical installations from Bhaktapur, where most of her artists come from. “Contemporary art is harder to sell,” she says plainly, “because it doesn’t represent a deity you can offer incense to.” So her gallery remains a haven for true enthusiasts—and a quiet hope that the country’s idea of art might one day evolve along with the country itself.

Which brings us to a striking contrast: the social divide that practically slaps you in the face here. The menu prices serve as both an invitation and a barrier. Having coffee here is a silent declaration that you’re not part of the rest. And the place itself shows that this divide is not only economic, but also historically entrenched.

The Baber Mahal complex still carries the spirit of the Rana era, when Nepal was ruled by an authoritarian dynasty from the mid-19th century until 1951. Their strategy: secure power through monopolizing education and information. Ordinary people were systematically denied access to knowledge—because an educated population was deemed too dangerous. The cost? A deeply rooted educational lag that persists to this day.

Those dark shadows haven’t lifted. On the way to the gallery, we passed teacher protests—demanding, loud, but peaceful. Their call: job security. In a country where trained teachers earn between 30,000 and 48,000 NPR (around €210–340 per month), other civil servants earn more—without bearing the same responsibility for society. Yet teachers can still be fired at any time. Employment on thin ice.

And yet education is everything—not just for personal development but for a nation’s future. Instead, many young Nepalis dream of one thing: studying abroad. And then? Moving far away—to work in Australia, Canada, or Europe. Nepal is exporting its brightest minds—willingly, but out of necessity. It may bring in short-term remittances, but in the long run, a country loses its soul if education leads not to roots, but to escape.

And that frustrates me. This country has everything: beauty, intellect, heritage, nature. Yet it’s losing its youth, its teachers, its hopefuls. And all in a time when education is key—to social progress, economic resilience, and democratic stability.

Humor is the last refuge, of course. So I sip what is—admittedly—a sinfully expensive espresso in Baber Mahal and ask myself:

How much art does a country need if it’s laying off its teachers?

Or the other way around: How much education does a country need to understand—and support—real art?

The two belong together. Sadly, all too often, only in theory.