Das Kastensystem in Nepal: Herkunft, Bedeutung und Wandel

Ein gesellschaftliches System, das so hartnäckig ist wie ein Himalaya-Winter

Nepal ist ein Land der Kontraste – majestätische Berggipfel und tiefe Täler, antike Tempel und moderne Smartphones, bescheidene Bauern und weltgewandte Trekking-Guides. Doch unter dieser Vielfalt verbirgt sich ein System, das älter ist als die meisten dieser Gipfel und genauso schwer zu überwinden: das Kastensystem.

Wie alles begann – ein göttlicher Bauplan für die Gesellschaft

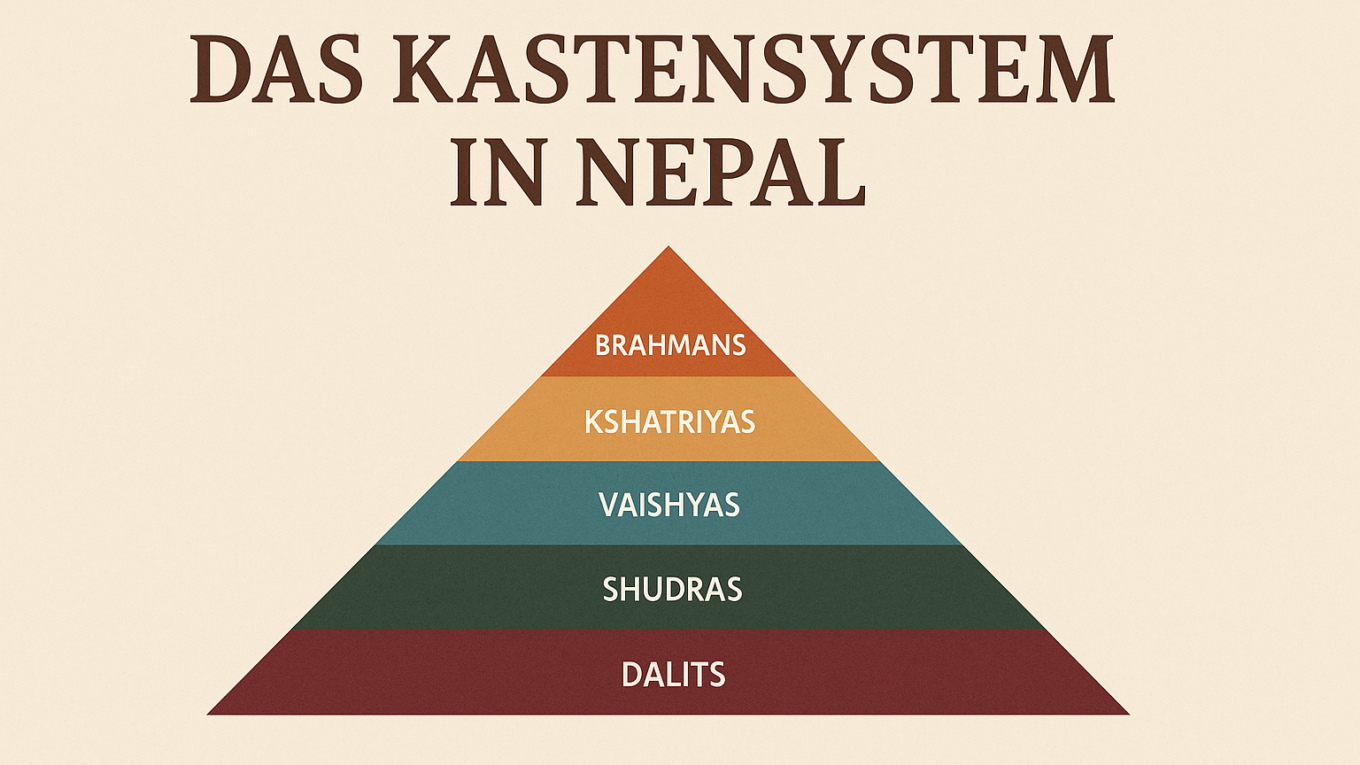

Das nepalesische Kastensystem hat seine Wurzeln im Hinduismus, genauer gesagt in einer Idee, die so alt ist, dass sie wahrscheinlich schon vor der Erfindung des Rades auf Steintafeln gemeißelt wurde: die vier Varnas. Diese mythologische Einteilung der Menschheit in Brahmanen (Priester), Kshatriya (Krieger), Vaishya (Händler) und Shudra (Diener) geht angeblich auf den Urmenschen Purusha zurück, dessen Körperteile die ursprünglichen „Kasten“ formten – Kopf, Arme, Beine und Füße. Dass in diesem Modell die Füße eindeutig die schlechtesten Karten hatten, ist offensichtlich. Wer will schon ein Zeh in der sozialen Hierarchie sein?

Doch Nepal wäre nicht Nepal, wenn es nicht eine eigene Variante dieses Systems entwickelt hätte. Während in Indien die Kastenordnung vor allem durch religiöse Schriften und gesellschaftliche Traditionen aufrechterhalten wurde, erhielt sie in Nepal durch das Muluki Ain von 1854 gesetzliche Weihen. Dieses erste nationale Gesetzbuch war so etwas wie die „Betriebsanleitung“ für Nepals Gesellschaft – allerdings eine, die man besser nicht laut vorlesen sollte, wenn Dalits in der Nähe sind. Es ordnete die gesamte Bevölkerung nach „reinen“ und „unreinen“ Gruppen, bestimmte, wer mit wem essen, trinken oder heiraten durfte und legte fest, wer als „unberührbar“ galt – ein System, das so undurchdringlich war wie der Dschungel im Terai.

Von Brahmanen und Bauern – wer oben steht, bleibt oben

In der Praxis bedeutete dies, dass Brahmanen und Chhetri (die nepalesischen Kshatriya) oben auf der sozialen Leiter standen, während die Dalits sich irgendwo darunter befanden – am Fuß der Leiter, um genau zu sein. Diese „Unberührbaren“ durften nicht nur keine höheren Kasten berühren, sondern oft nicht einmal dieselben Brunnen benutzen oder dieselben Tempel betreten. Die logische Konsequenz war eine Gesellschaft, in der die soziale Mobilität etwa so wahrscheinlich war wie ein spontaner Schneefall im Kathmandu-Tal.

Doch die Kastenordnung war nicht nur vertikal, sondern auch horizontal ausdifferenziert. So gab es in Nepal neben den klassischen hinduistischen Kasten auch zahlreiche ethnische Gruppen, die in das System eingegliedert wurden, ob sie wollten oder nicht. Die Newar zum Beispiel, die ursprünglichen Bewohner des Kathmandu-Tals, entwickelten ihr eigenes Kastensystem, das teilweise noch komplexer ist als die ursprüngliche Hindu-Variante. Selbst die tibetisch-buddhistischen Sherpa – bekannt als die unerschrockenen Gipfelstürmer des Himalaya – blieben nicht ganz verschont, auch wenn ihre gesellschaftlichen Hierarchien etwas durchlässiger sind.

Das Kastensystem trifft auf die Moderne – ein ungleiches Duell

Doch wie jedes starre System geriet auch das nepalesische Kastensystem irgendwann ins Wanken. Ab Mitte des 20. Jahrhunderts begann die Welt, sich schneller zu drehen, und die alten Hierarchien bekamen Risse – nicht zuletzt, weil die Ranas, die eigentlichen Machthaber Nepals seit dem 19. Jahrhundert, ihre feudale Herrschaft verloren und die Monarchie wieder zu politischer Macht kam.

1951, nach einer kurzen, aber intensiven Volksrevolte, musste die nepalesische Aristokratie plötzlich feststellen, dass Bauern und Handwerker nicht nur nützliche Steuerzahler sind, sondern gelegentlich auch politische Forderungen stellen. Es folgten Reformen, die das alte Kastensystem formal abschafften – zumindest auf dem Papier. Die Verfassung von 1962 erklärte alle Bürger für gleich, und die Anti-Diskriminierungsgesetze von 1990 und 2015 gingen sogar noch weiter, indem sie „Unberührbarkeit“ explizit verboten.

Doch wie so oft in der Geschichte gilt auch hier: Nur weil etwas verboten ist, heißt das nicht, dass es nicht mehr existiert. Obwohl die Kastentrennung offiziell passé ist, bleibt sie in den Köpfen vieler Nepalesen lebendig. Die gesellschaftlichen Hierarchien, die über Jahrhunderte gewachsen sind, lassen sich nicht so einfach wegwischen wie der Staub auf einem Trekking-Rucksack. In vielen ländlichen Gemeinden ist die Kaste noch immer ein wichtiger Faktor bei der Berufswahl, der Partnerwahl und sogar bei der Frage, wer auf welcher Seite des Dorfbrunnens Wasser holen darf.

Von Dalits und Doktoren – wenn Vorurteile die Karriere behindern

Ein typisches Beispiel: Ein Dalit, der es irgendwie geschafft hat, eine gute Ausbildung zu bekommen und als Arzt oder Ingenieur zu arbeiten, wird oft dennoch diskriminiert – sei es durch subtile Vorurteile oder offene Ablehnung. „Du hast vielleicht einen Doktortitel, aber du wirst immer ein Dalit bleiben“ – solche Sätze fallen nicht nur hinter vorgehaltener Hand. Und während Interkaste-Ehen in den Städten langsam zunehmen, können sie in ländlichen Gebieten immer noch zu sozialen Konflikten führen, die nicht selten blutig enden.

Und jetzt? Ein Blick in die Zukunft – zwischen Hoffnung und Tradition

Doch es gibt auch Hoffnung. Die jüngere Generation Nepals ist weniger an den alten Regeln interessiert als ihre Eltern und Großeltern. In den Städten, wo Menschen aus verschiedenen Regionen und Hintergründen zusammenleben, verliert die Kaste zunehmend an Bedeutung. Wer in Kathmandu, Pokhara oder Biratnagar lebt, interessiert sich oft mehr für seine Instagram-Follower als für die Kaste des Nachbarn. Bildung, Mobilität und das Internet tun ihr Übriges, um die alten Barrieren aufzubrechen – wenn auch langsamer, als vielen lieb wäre.

Aber auch die Regierung tut inzwischen mehr, als nur gute Absichten zu verkünden. Quotenregelungen für Dalits in lokalen Gremien und politischen Parteien, staatliche Förderprogramme für benachteiligte Gruppen und eine wachsende Zahl von Dalit-Aktivisten, die lautstark ihre Rechte einfordern, zeigen, dass der Wandel real ist – auch wenn er oft so zäh verläuft wie ein Lastwagen auf einer Bergstraße.

Fazit – Ein System auf dem Prüfstand

Das nepalesische Kastensystem ist noch längst nicht Geschichte, aber es verliert langsam an Einfluss. Die nächste Generation wird entscheiden, ob es endgültig in die Geschichtsbücher verschwindet oder sich in neuer Form anpasst – wie ein altes Gurkha-Messer, das immer wieder geschliffen wird, aber nie ganz stumpf wird. Vielleicht wird eines Tages die Frage „Welcher Kaste gehörst du an?“ in Nepal so antiquiert wirken wie die Frage „Welches Faxgerät benutzt du?“. Bis dahin aber bleibt die Kaste ein Teil der nepalesischen Realität – ein System, das so hartnäckig ist wie ein Himalaya-Winter und so schwer abzuschütteln wie der Staub auf einem Trekkingpfad.

English version below

The caste system in Nepal: origin, meaning and change

A social system as stubborn as a Himalayan winter

Nepal is a land of contrasts – majestic mountain peaks and deep valleys, ancient temples and modern smartphones, humble farmers and urbane trekking guides. But beneath this diversity lies a system that is older than most of these peaks and just as difficult to overcome: the caste system.

How it all began – a divine blueprint for society

The Nepalese caste system has its roots in Hinduism, more precisely in an idea that is so old that it was probably carved on stone tablets before the invention of the wheel: the four varnas. This mythological division of humanity into Brahmin (priest), Kshatriya (warrior), Vaishya (merchant) and Shudra (servant) supposedly goes back to the primal man Purusha, whose body parts formed the original „castes“ – head, arms, legs and feet. It is obvious that the feet clearly had the worst cards in this model. Who wants to be a toe in the social hierarchy?

But Nepal would not be Nepal if it had not developed its own version of this system. While in India the caste system was upheld primarily through religious scriptures and social traditions, in Nepal it was consecrated by law in the Muluki Ain of 1854. This first national code was something like the „instruction manual“ for Nepal’s society – albeit one that is best not read aloud when Dalits are around. It categorised the entire population into „pure“ and „impure“ groups, determined who was allowed to eat, drink or marry with whom and defined who was considered „untouchable“ – a system that was as impenetrable as the jungle in the Terai.

Brahmins and peasants – whoever is on top stays on top

In practice, this meant that Brahmins and Chhetri (the Nepalese Kshatriya) were at the top of the social ladder, while the Dalits were somewhere below – at the bottom of the ladder, to be precise. Not only were these ‚untouchables‘ not allowed to touch higher castes, but often they were not even allowed to use the same wells or enter the same temples. The logical consequence was a society in which social mobility was about as likely as a spontaneous snowfall in the Kathmandu Valley.

However, the caste system was not only differentiated vertically, but also horizontally. In addition to the traditional Hindu castes, there were also numerous ethnic groups in Nepal that were incorporated into the system whether they wanted to or not. The Newars, for example, the original inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley, developed their own caste system, which in some cases is even more complex than the original Hindu version. Even the Tibetan Buddhist Sherpa – known as the intrepid summiteers of the Himalayas – were not completely spared, even if their social hierarchies are somewhat more permeable.

The caste system meets modernity – an unequal duel

However, like any rigid system, the Nepalese caste system also began to falter at some point. From the middle of the 20th century, the world began to turn faster and the old hierarchies began to crack – not least because the Ranas, the real rulers of Nepal since the 19th century, lost their feudal rule and the monarchy regained political power.

In 1951, after a brief but intense popular revolt, the Nepalese aristocracy suddenly realised that farmers and artisans were not only useful taxpayers, but also occasionally made political demands. Reforms followed that formally abolished the old caste system – at least on paper. The 1962 constitution declared all citizens equal, and the anti-discrimination laws of 1990 and 2015 went even further by explicitly banning „untouchability“.

But as so often in history, the same applies here: Just because something is banned doesn’t mean it no longer exists. Although caste segregation is officially passé, it remains alive in the minds of many Nepalese. The social hierarchies that have grown over centuries cannot be wiped away as easily as the dust on a trekking rucksack. In many rural communities, caste is still an important factor in the choice of profession, choice of partner and even in the question of who is allowed to fetch water on which side of the village well.

Dalits and doctors – when prejudices hinder careers

A typical example: a Dalit who has somehow managed to get a good education and work as a doctor or engineer is often still discriminated against – whether through subtle prejudice or open rejection. „You may have a doctorate, but you’ll always be a Dalit“ – such sentences are not only uttered behind closed doors. And while inter-caste marriages are slowly increasing in the cities, in rural areas they can still lead to social conflicts that often end in bloodshed.

And now? A look into the future – between hope and tradition

But there is also hope. Nepal’s younger generation is less interested in the old rules than their parents and grandparents. In the cities, where people from different regions and backgrounds live together, caste is becoming less and less important. People living in Kathmandu, Pokhara or Biratnagar are often more interested in their Instagram followers than in their neighbour’s caste. Education, mobility and the internet are doing their bit to break down the old barriers – albeit more slowly than many would like.

But the government is now also doing more than just proclaiming good intentions. Quota regulations for Dalits in local committees and political parties, state support programmes for disadvantaged groups and a growing number of Dalit activists who are loudly demanding their rights show that change is real – even if it is often as slow as a lorry on a mountain road.

Conclusion – A system under scrutiny

The Nepalese caste system is far from history, but it is slowly losing its influence. The next generation will decide whether it disappears into the history books for good or adapts in a new form – like an old Gurkha knife that is sharpened again and again but never becomes completely blunt. Perhaps one day the question „Which caste do you belong to?“ will seem as antiquated in Nepal as the question „Which fax machine do you use?“. Until then, however, caste remains a part of Nepalese reality – a system that is as stubborn as a Himalayan winter and as hard to shake off as the dust on a trekking trail.